He was a regular on HBO’s popular program “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” where he quarreled and bitched with his boyhood buddy Larry David.

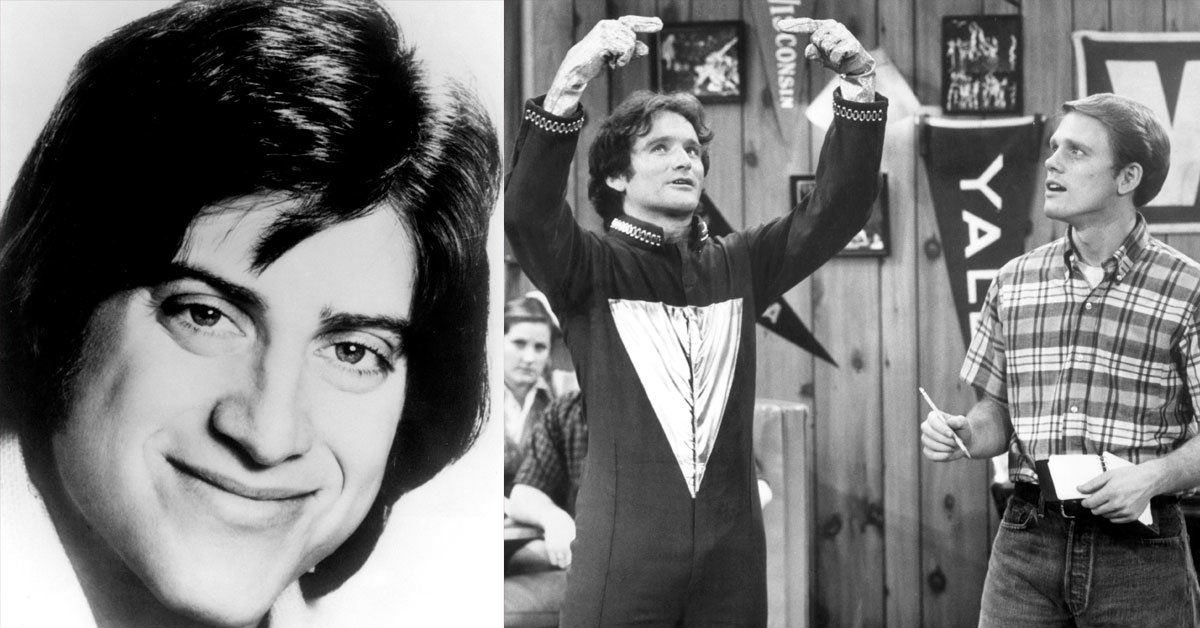

Richard Lewis, the all-black stand-up comedian who played a semi-fictionalized version of himself on HBO’s “Curb Your Enthusiasm” and who named some of his cable specials “I’m in Pain,” “I’m Exhausted,” and “I’m Doomed”—died on February 27 at his Los Angeles home. Lewis was known for mining guilt, anxiety, and neurosis for laughs. He was seventy-six.

According to his spokesman Jeff Abraham, Mr. Lewis passed away due to a heart attack. When Mr. Lewis said in April that he was giving up stand-up, he disclosed that he had been dealing with Parkinson’s disease since 2021 and that he had undergone “back-to-back-to-back-to-back” surgery on his hip, back, and shoulder.

Mr. Lewis, a self-deprecating comedian with a head of thick, dark hair that he frequently nervously ran his hands through, became well-known across the country for his television specials from the 1980s, in which he related tales of his turbulent upbringing and failed romances while cautioning viewers that “life isn’t supposed to be great all the time.”

In addition, he was cast in comedy roles. In Mel Brooks’s parody film “Robin Hood: Men in Tights,” he played Prince John, a comically avaricious ruler with a migrating mole that mysteriously moves across his face. He costarred with Jamie Lee Curtis as a Chicago magazine columnist in the sitcom “Anything But Love” (1989–1992).

He was most likely best known to younger audiences as the melancholy cornerstone of “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” the highly improvisational sitcom that starred and was produced by his boyhood buddy Larry David, who also co-wrote “Seinfeld.” Both in reality and in art, the two were always bickering, riffing, and kvetching: The show, which debuted in 2000 and is currently in its 12th and final season, features episodes in which Mr. Lewis’s character has to put up with humiliations like being carjacked by a fan of the New York Jets, convinces a deli owner to rename a sandwich from Larry David to Richard Lewis, and gets upset about unfiltered tap water being served at a dinner party.

“L.D., goldfish would commit suicide in this water,” he says to David.

The two comedians “hated each other,” Mr. Lewis told The Washington Post in 2020, when they first met at a summer camp in Cornwall-on-Hudson, New York, when they were 12 years old. He was a lanky, loud, and bothersome basketball player. I shot the target better. However, humor brought them back together in the early 1970s, when Mr. Lewis was doing some of his earliest stand-up routines and attending Greenwich Village open-mic nights in addition to his day job as a copywriter for a Hasbrouck Heights, New Jersey, advertising firm.

He appeared on a tour with Sonny and Cher and gained further recognition at comedy clubs in Los Angeles thanks to the support of fan and comedian David Brenner. Additionally, he was introduced to George Schultz, the owner of a comedy club in Brooklyn. According to the Record newspaper in New Jersey, Schultz allegedly gave Rodney Dangerfield the “no respect” line. Mr. Lewis was encouraged to change the tone of his stand-up by incorporating some of the psychological torment that inspired his comedy.

Mr. Lewis famously joked, “Honestly, the reason I went onstage is to have people listen to me talk about my feelings without someone saying, ‘Pass the meatloaf.'”

Mr. Lewis had been a regular on Johnny Carson’s “The Tonight Show” since the mid-1980s (“I have dandruff, it’s a bad start,” he admitted to the audience), and he was being mentioned alongside other irreverent and sometimes self-reflexive comics like Richard Pryor, George Carlin, and Lily Tomlin. According to Journey Gunderson, the executive director of the National Comedy Center, “his work exemplified and anticipated the deeply personal, raw, introspective and yes, neurotic, tone that has come to color so much contemporary comedy.”

On his computer, Mr. Lewis estimated that he had “about 20,000 pages” of jokes. He wrote notes on legal pads early in his career. In 1989, when he performed at Carnegie Hall, he came out on stage with six feet of yellow sheets taped together on the ground as a guide. The two standing ovations he got were described by him as “the highlight of my career.”

Mr. Lewis claimed that later that evening, when intoxicated in the venue’s dressing room, he had to ask his sister whether the applause had really happened. That, in his own words, marked the start of his protracted battle to cut back on his drinking, which he detailed in his 2000 book, “The Other Great Depression.” The book was published a few years after he sobered up, he said, following a well publicized humiliation in 1999 when he was listed as “Actor, Writer, Comedian, Drunk” on a prominent alumni page in Ohio State University’s basketball media guide.

According to Mr. Lewis, the experience provided an additional challenge to his sobriety, and he discovered that humor and openness were beneficial.

In 2001, he told the Chicago Tribune, “I really did burn many bridges—I mean, I’ve lost a lot [of] friends.” However, I felt that I owed it to myself to admit my addiction to booze. Since I’ve always been as truthful as I possibly could be while performing on stage. However, I also spent a lot of that period in denial.

Richard Philip Lewis, the youngest of three children, was reared (or “lowered,” as he described it) in Englewood, New Jersey. He was born in Brooklyn on June 29, 1947. According to Mr. Lewis, his father, a caterer, was so preoccupied with his work that “he was booked on my bar mitzvah—and I had my party on a Tuesday.”

His mother, who performed in local theater, found it difficult to comprehend why he was interested in comedies. Mr. Lewis said that during one act, “I made a joke about my father having 12 heads. “That’s a load of crap,” said my mother as she got to her feet. Ultimately, she warmed up to his antics, saying in 1990 to GQ, “Now, if he doesn’t mock me, I feel insulted.” (He once mentioned that she had “major open-guilt surgery” to recuperate from.)

Mr. Lewis attended Ohio State to study marketing, graduating in 1969 with a bachelor’s degree. He claimed that he didn’t start concentrating on stand-up until his father passed away in 1971. He said to USA Today, “There was such a void, and ironically, I thought I had nothing to lose.”

He co-wrote and acted in “Diary of a Young Comic,” a 90-minute TV film that aired on NBC in 1979 as a stand-in for “Saturday Night Live,” turning his early troubles with stand-up into written humor. Mr. Lewis portrayed Billy Gondolstein, a young New York comic who, like Mr. Lewis, moves west to Los Angeles and changes his last name to Gondola in an attempt to gain notoriety and money.

After a few years, Mr. Lewis adopted his trademark all-black ensemble, claiming that it was modeled after the monochromatic Paladin persona worn by Richard Boone in the TV western “Have Gun— Will Travel,” which was a boyhood favorite of his.

In television, he played a psychologist in the short-lived Fox sitcom “Daddy Dearest” (1993) who lives in New York with his abusive father (Don Rickles). He also made a brief appearance in the drama “Leaving Las Vegas” (1995) as a business partner of Nicolas Cage’s character, an alcoholic screenwriter.

Mr. Lewis, who was well-known for his tendency to date repeatedly and his fear of being committed, met music publishing executive Joyce Lapinsky at an album release party for Ringo Starr. Seven years later, in 2005, they were married after he took her to see his therapist to get his blessing. “This is as good as it gets!” the therapist yelled at him, according to what he told her. It just floored me. His brother and wife are among the survivors.

Mr. Lewis never wavered from his sharp and self-deprecating sense of humor as he grew older.

He remembered talking with movie star John Travolta, who attended the same Englewood high school, during a 1988 Record interview. Mr. Lewis stated, “He was saying that he was sure that they had named a gymnasium after him.” “I reasoned that perhaps there are a few bridge chairs in the faculty lounge that bear my name. The nurse’s office bench is what I should have.

He went on, “I don’t want to sound like a big shot.” “At least I should be able to have people sit on me after 45 shows on Letterman and 16 years of complaining.”

Salvatore Matthias

Legal Nation Wide THCA FLOW, Ounces Starting at 60 dollars Pounds at 900 https://thcaking.com/?ref=027m2bvn

gummies de cbd 20 gomitas - newpharma

best kik delta 8